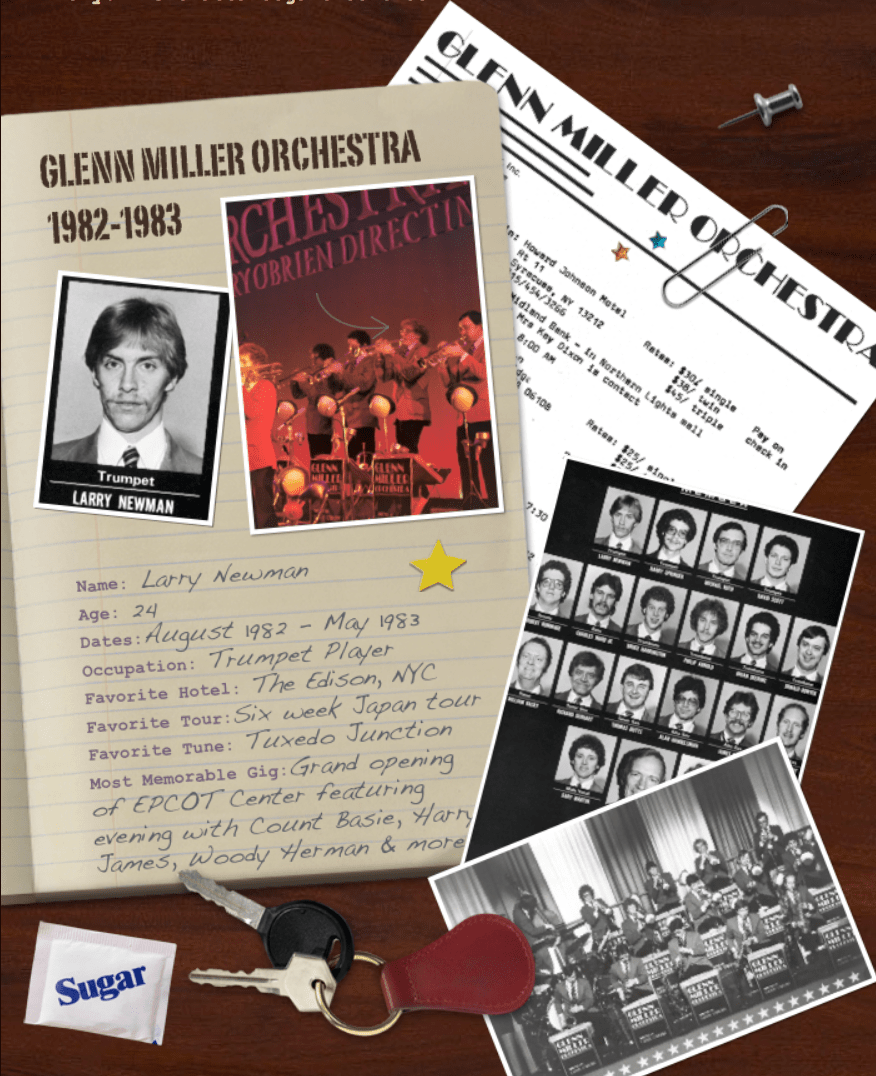

By John Willard of the Quad-CityTimes, Davenport, Iowa

A three-part series published in October 1982

PART ONE • PART TWO • PART THREE

ON THE ROAD WITH THE GLENN MILLER ORCHESTRA

The rugged valleys of southwestern Wisconsin are aflame with fall colors, but the beauty is lost to the people of various contorted positions in their seats aboard the “Chattanooga Choo Choo.”

This “Chattanooga Choo Choo” is a bus – not a train. It is a clothing-crammed home on wheels for the 19 members of the Glenn Miller Orchestra, a “ghost” band keeping alive the memory of one of America’s most beloved bandleaders.

The musicians, accompanied by a reporter, are catching up on precious sleep as the silver-and-blue GM coach hurtles toward a concert date in Hastings, Minn.

It’s 7:15 a.m. on a misty Sunday. We’re on Interstate 90 somewhere between LaCrosse, Wisconsin, and the last chorus of “Tuxedo Junction.” Eight hours earlier, the boys (and one girl) on the bus kept a capacity crowd stomping to that Glenn Miller tune and many others at a homecoming dance at Northwestern University in Evanston, Ill.

And the night before that, more than 900 people heard the band at Davenport’s Colonial Ballroom, where a revolving mirror ball sent splashes of starlight skittering across the polished dance floor. Suddenly it was the late 1930’s, the period when the original Glenn Miller band enjoyed superstar status.

But when the musicians returned to their Davenport hotel it was 1982. The next afternoon, they were on the road to Evanston.

The Northwestern University gig was, in band parlance, a “hit and run.” After the four-hour dance ended at 1:30 a.m., the musicians loaded up the bus and hit the road for the 400-mile journey to Hastings. They didn’t have the luxury of returning to a hotel room.

Of the Glenn Miller Orchestra’s nightly concert or dance dates, as average of three a week are “hit and run” performances. The band is on tour 50 weeks a year.

LIFE ON THE ROAD is a grueling existence. It is a succession of one-night stands, bouncing bus rides, motel rooms (with band members frequently doubling and tripling up to save money) and restaurants that all seem cloned.

This “Chattanooga Choo Choo” is a bus, not a train. It is a clothing-crammed home on wheels for the 19 members of the Glenn Miller Orchestra, a “ghost” band keeping alive the memory of one of America’s most beloved bandleaders.

Each musician is assigned a pair of seats so that he has enough room to sleep. But two narrow seats hardly make a queen-size mattress. Orchestra members become skilled acrobats as they squeeze themselves into sleeping positions, placing pillows at strategic points under their bodies.

ON THIS TRIP, the blue-jeaned legs sprawled across the aisle resembling sacks of flour. The arch of out-stretched male legs is interrupted by the sheer pantalooned gams of Colleen Miller, the band’s 23-year-old vocalist.

“Being the only woman on the bus can be a problem, but the guys are quite understanding,” Miss Miller says. She is a theater graduate of Boston Conservatory of Music, and her father sang in a big band during the 1940s.

Miss Miller has her own motel room on the road, and efforts always are made to secure her a private dressing room. The men change on the bus.

“Actually, all I need is a place to plug in my electric hair curler,” says Miss Miller

The “road rats” of the Glenn Miller Orchestra have learned to adapt to their hectic life on wheels. At a time when big band sounds of the 1930s and 1940s are making a comeback on radio stations, the Glenn Miller “ghost” band never has been more popular. Orchestra members seem proud of their roles as curators of a musical treasure.

THE TRADITION goes back to 1937 when Iowa-born trombonist and arranger Alton Glenn Miller organized his first band. Miller had played with Tommy and Jimmy Dorsey and other stars of the “swing’ era.

While on his own, he developed a distinctive sound by blending a clarinet with four saxophones. As the clarinet and saxes held the melodic line, growling trombones and wailing trumpets added their “ooh-ahs.” The Modernaires – Tex Beneke, Ray Eberle and Marion Hutton – provided vocals.

Miller’s lush ballads and crisp, driving swing numbers were immensely danceable. At places like the Glen Island Casino and the Cafe Rouge of New York City’s Pennsylvania Hotel, couples waltzed and jitterbugged to such Miller hits as “In the Mood, ”“Moonlight Serenade,” Chattanooga Choo Choo” and “String of Pearls.” By 1939, Millers records on the RCA VIctor label consistently topped the charts.

WHEN WORLD WAR II broke out, Miller joined the U.S. Army and organized his famed Army Air Forces Band. WIth such tunes as “St. Louis Blues March” and “American Patrol,” the band did much to boost morale of troops overseas.

Maj. Miller paid the ultimate price for his patriotism. On Dec. 15, 1944, the 40 year-old bandleader vanished with a military plane flying from England toward France.

The Glenn Miller Orchestra currently is led by Larry O’Brien, 49, a one-time trombonist with the band. O’Brien’s other musical credits include stints with Frank Sinatra Jr., Nelson Riddle and Ralph Marterie.

ALTHOUGH it attracts a few seasoned veterans, the Glenn Miller Orchestra is mainly a training ground for young, college-educated musicians. Their average age is 24, a fact that surprises audiences. “Most people expect us to come out in wheelchairs,’ road manager and saxophone section leader Richard “Zoot” Gearhart says.

The starting pay is $300 a week, although orchestra members can earn as much as $500 depending on experience and other duties with the band. They also must pay for their own lodging and meals.

Because the pay is considered low for a big name band, the Glenn Miller Orchestra has a high turnover. Most sidemen stay less than a year, and new faces appear in the band almost every week.

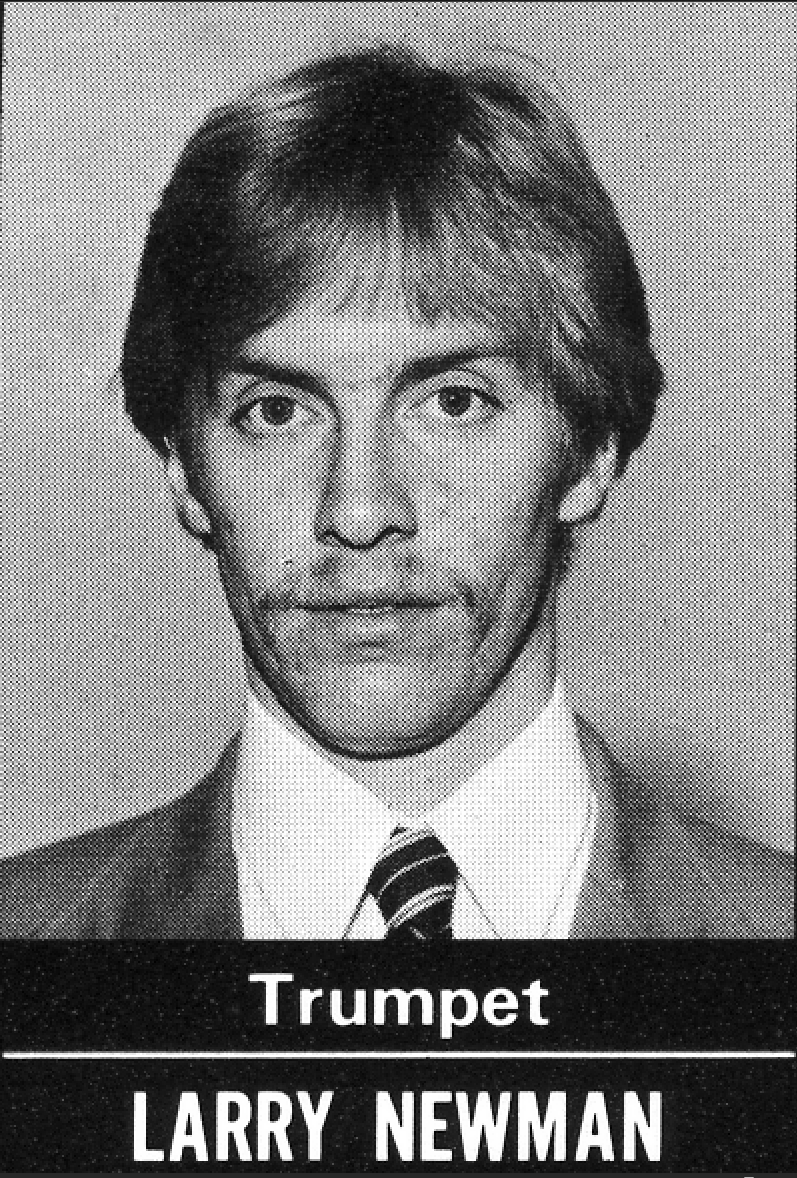

Spilt-lead trumpeter, Larry Newman, 23, joined the band just a few months ago, but he is already the veteran player in the trumpet section.

“I have seen new players in the trumpet section almost every two weeks since I joined the band. I’m still feeling new – but the other guys in the section have been here less time than me.” Newman said.

I’m hoping our present section will stick around for awhile – at least through the Japan tour coming up this spring.”

For all the turnover, the Glenn Miller Orchestra has no trouble filling its ranks. Young musicians try out for the band for the experience, prestige and travel opportunities. To older players, the Glenn Miller Orchestra means steady work at a time when full-time musicians’ jobs are scarce.

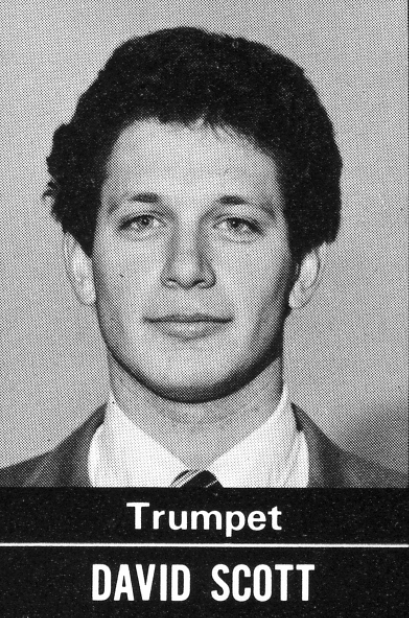

The band’s current roster includes lead trumpet player David Scott, 23, Knoxville, Iowa, a music graduate of the University of Iowa. Scott was hired after auditioning at Anaheim, Calif., where he had been playing with the Disneyland Orchestra.

THE ONE-TIME member of the Hawkeye Marching Band and the Quad-Cities Jazz Ensemble talked about life in the Glenn Miller Orchestra.

“It’s a 24-hour job,” he says. “We change clothes on the bus, we sleep on the bus, we live on the bus. But Glenn Miller is an institution. I’m happy to help keep this tradition alive.”

Scott and his fellow musicians presented music history to a sell-out crowd at the Col. The dancers included Scott’s parents, Marilyn and Donald Scott, who drove all the way from Knoxville. The Scotts beamed with pride as their son stepped to the front of the bandstand for his muted solo on “Tuxedo Junction.”

I think Dave’s getting solos because the leader knows his mother and father are here,” Mrs. Scott said modestly.

In their spiffy blue jackets, neckties and dark trousers, members of the Glenn Miller Orchestra were the center of attention as the predominantly middle-aged crowd at the Col relived their youth with such tunes as “Little Brown Jug,” “At Last” and “Serenade in Blue.” A few contemporary tunes like Billy Joel’s “I Love You Just the Way You Are” were thrown in.

THE NEXT NIGHT at Northwestern University, it was obvious that the Glenn Miller sound was won a whole new generation of fans. The setting for the homecoming dance was a tent perched on a terrace of the college’s stunning new student center overlooking Lake Michigan. Sprits were high because the Wildcats had won their first Big Ten football game in five years.

Under a big top festooned with purple and white Christmas tree lights and bunches of purple and white balloons, students, several in period dress, twisted through jitterbug routines their parents probably didn’t know existed. As searchlights played on low-hanging clouds and reflections from street lights danced in the shimmering lake, one easily could imagine people alighting from Packards and LaSalles at the Glen Island Casino.

But the magic soon ended. After the dance was over, musicians of the Glenn Miller Orchestra returned to the drudgery of loading up boxes of sound gear and music stands into the cargo hold of the “Chattanooga Choo Choo.” Once again, they were road rats.